This Friday just gone, after many months of waiting, I finally got to take the family up to the Royal Academy in London to see David Hockney’s mega-exhibition ‘A Bigger Picture’. I say finally, because despite having known about the exhibition way back last year, it was only in mid-January that everyone in my family could agree that they wanted to come, and by then the earliest we could book tickets was for the end of March. Such is the popularity of the man and his art.

Let me start by saying that this is a hugely enjoyable exhibition, and most people in the RA were having a good time and enjoying themselves. The galleries were very full of visitors, but not overcrowded, and you could easily get a good view of the pictures you wanted to see. The images were presented in a wide smorgasbord of media; oils, watercolours, charcoals, photos, iPad images (printed & actual iPads) and multipanel HD video screens.

I’m a big fan of Hockney’s work, especially his landscape and joiner images, so this show was a real treat for me. I love the bold shapes and graphic simplicity of his landscapes, the swooping hills and the animated trees. But it’s the colour that hits you most. On some painting the colours are so intense, so bright that you can find it hard to believe that anyone could dare to use them. For instance, in the first gallery of early landscapes, A Closer Grand Canyon has the most amazing, supersaturated oranges and yellows that can hardly be said to be realistic. But that intensity of colour does evoke the glorious sunsets, the scorching heat, the amazing space of the real Grand Canyon.

Just behind The Bigger Canyon were three of Hockney’s joiners – two of Grand Canyon and a less often seen or reproduced version of Pearblossom Highway. It was great to see these collages, especially Pearblossom which is a landmark image for me. But I have to admit to a little bit of disappointment. Maybe I should have worn sunglasses when looking at A Bigger Canyon, but these photocollages were dimly lit, and the colours seemed to be fading. Indeed, reproductions of Pearblossom on sale in the RCA shop seemed to have better saturation.

After this historical scene-setting you then enter the many halls of Hockney’s modern Yorkshire pictures, which are wonderful, fresh and vital. It is thrilling to see a man in his seventies working with such energy and enthusiasm. There is hope for us all cometh the day! Again, there are the signature bold, deft brush marks and that amazing use of colour, from the brightest oils to more gentle watercolours, is always keenly observed, and used to intensify the visual experience.

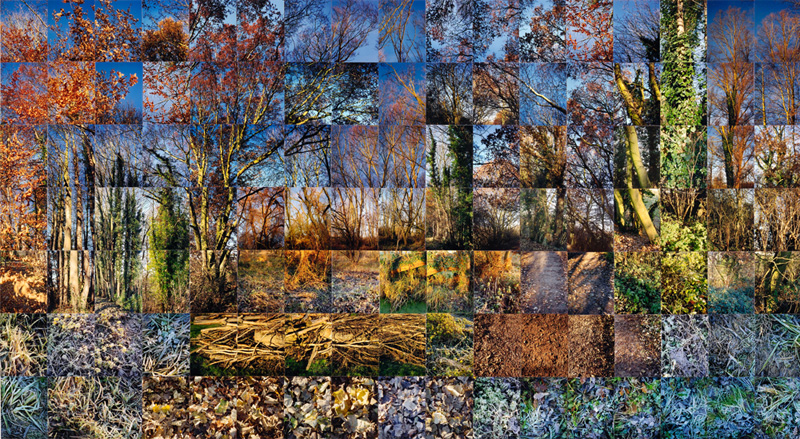

Hockney has chosen several key locations for his work, and has returned time and again to make images in all seasons. There the Thixendale Trees that greet you as you enter the exhibition, the Woods at Woldgate, a tree lined track christened by Hockney as ‘The Tunnel’. All of these are captured in different lights in different seasons, and all the time there is this wonderful visual sensation of being there, sensing the light and the enjoyment Hockney got from looking at the scene.

The culmination of the exhibition is the Arrival of Spring, Woldgate 2011; a room full of large scale iPad reproductions running in chronological order from the New Year to, well, the Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, which is delivered in a huge, glorious and vivacious, multi-panel oil painting.

Almost as an adjunct to the exhibition, as if he had done an experiment and thought ‘you have got to see this’, is a large room with one wall covered in a six wide, three deep array of large HD videoscreens. Hockney has been strapping 3X3, and then 3X6 cameras to the side or front of his jeep and driving down country lanes at slow speed to film the location. Each camera is given a slightly different viewpoint and focal point. As with his photo joiners, there are overlaps and some duplication. But they are synced together perfectly time-wise. I had seen some of these images reproduced in books, and frankly was sceptical. It seems to me that 3X3 is too coarse for a still joiner to work. But the sensation as a video image was a revelation. These short sequences looked amazingly three dimensional. Leaves and branches rendered out of focus on one panel would pass onto the next panel sharply resolved. I can’t see this approach being adopted by film or television producers, but it was a captivating visual experience. Interestingly, this sensation evaporated if you were to cover one eye. Sight and perception is an interesting and complex area, and as ever, Hockney is at the forefront of exploring this subject from an artistic viewpoint.

We spent an hour and a half taking in the whole exhibition. Our feet and legs were tired from all the shuffling around, but we all enjoyed ourselves. For me, the highlight of the show was having the company of my 11 year old son all the way around, discussing the works and listening to him thrill to the pictures. Because if art is to be anything, it is about the communication of ideas and feelings, and David Hockney had achieved that. Forget about the pompous, pretentious stuff that masquerades as art these days and is more an intellectual joke than anything else. This is art that we can all make an effort to understand, we can all feel, and everyone can enjoy.