|

Dike and field with last snow, Holland 1996 ©

Ger Dekkers

|

A few years ago we spent a very enjoyable autumn half term

with the family staying in an apartment at The Hague in the Netherlands. During our

visit we visited FOAM, the Dutch photo museum to see an excellent exhibition of

early Hungarian photos by Kertesz, Martin Munkácsi, Moholy-Nagy and others. In the

bookshop I came across some intriguing postcards by Dutch landscape

photographer Ger Dekkers. I was immediately struck by the geometry of his work,

and bought a few.

Dekkers works in carefully orchestrated sequences of

pictures, and has two basic approaches. The first is a linear sequence of

pictures taken from different, sequential, viewpoints. As we all know from our

geography lessons the Netherlands is a highly populated country, so when

travelling on back roads through the countryside the hand of man is everywhere

to be seen. Fields are carefully manicured and well-tended, often lined with

trees and fences. Because the land is so flat, most field boundaries, hedges,

stands of trees following straight lines, designed by man. As you travel

through the landscape recurrent patterns appear, disappear and reappear. To me,

this felt rhythmic and reassuring rather repetitive and boring as you find in

larger lands. As you watch the unfolding scene you see that there is no definitive

viewpoint, no decisive moment that encapsulates the view. Rather, there are

many points that are equally acceptable. Dekkers’ work plays with this concept

of views in transit by creating a sequence of five to seven pictures taken from

a series of points that describe a similar view. The baseline concept is to

place distant landmarks (farmhouses, the horizon) in exactly the same position

in each frame, whilst using strong graphical entities (plough lines, stands of

trees) to move through subsequent frames. Dekker uses a medium format camera

frequently with a widish lens to further emphasise convergent lines.

|

Cycle-track,

near Dronten, Holland 1998 ©

Ger Dekkers |

|

The results are interesting. Because of their linear

arrangement the pictures can read as set of very large frames from a movie,

giving a dynamic cinematic feel to the resulting set. Individually the pictures

are rigorously framed, well lit and attractive enough as images in their own

right. Together they often work together to create a pattern en masse. At times he creates an

interesting faux-panoramic effect because the sequence looks wide, but the

movement around the distant centre of focus is actually quite small. The

overall impression is of travelling through the landscape, of building up a

visual memory from several viewpoints, to get a better understanding of the

subject and the space surrounding it.

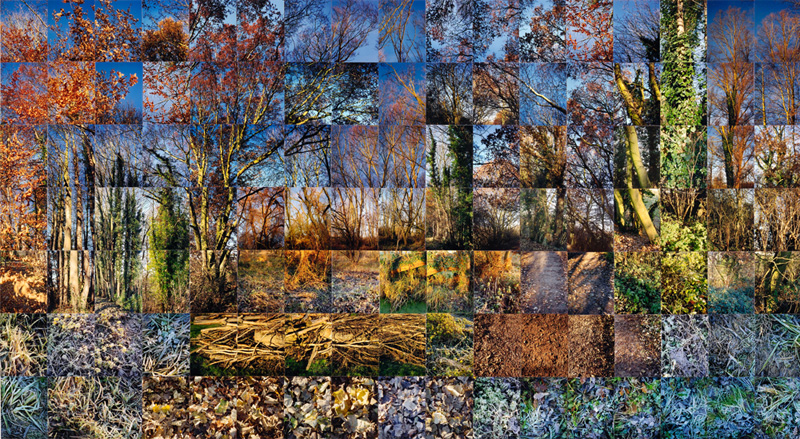

His second approach is to stand at a fixed viewpoint and

slightly vary the direction of view and hence the framing of the scene. The

intention here seems to be to create a pleasing or interesting geometric

pattern within a 3×3 grid.

Dekkers creates a pattern that shows increasing variation diagonally from top

left cell to bottom right. It would appear that the ploy adopted by Dekkers was

to successively pan the camera downwards in equal increments and then place

these left to right in successive rows running top to bottom. Whilst I prefer

the narrative of his linear compositions, these grid patterns work, again, by

repetition and reinforcement, this time achieved by multiple framings. The

linear sequences are ideally suited to regular geometry, but the grid method

would work with any subject.

|

Breakwater,

Pietersbierum, Holland 1996 ©

Ger Dekkers |

These three postcards from Holland have been niggling away

at the back of my mind for some time now, so I’ve tried researching Dekkers’

work to understand more about his work, methods and ideas. Dekkers is now 83,

and judging from the lack of information about him on the web, no longer an

active photographer. He has no website, no entry in Wikipedia and at first the

only mentions I could find about him were mainly from secondhand and rare book

dealers, and a few art listings that gave little more information other than

his age and nationality. I have one book in my little library that mentions his

work, but with very little useful information. So I decided to buy a book

though Abebooks. I ended up with a very slim catalogue Landscape Perspectives from an exhibition held in 1976, bought from

a bookshop in Essex - the only volume of his work that was available in the UK.

Although the printing is rather poor and the paper discoloured, it does give a

fascinating glimpse in to the work of a man, whose work was quite well known in

its day, judging by the quality of the museums that showed his work, and the

number of books that bore his name.

After a bit more rooting around on the internet I did

eventually find one good resource about Dekkers and his work at Depth of Field.

Google Translate makes a reasonable fist of translating this resource from the

Dutch original, and shows that his work was given some very high profile

displays, including very innovative large format slide

projections in the 70s. In addition to describing his working methods, it talks

about his fascination with the new territories created in the post-war polders.

The main framework of his imagery was the creation of this new, man-made land,

and his work resonated with Dutch in their pride of their national achievement.

Although some of his images are still available as postcards

and posters in Holland, there seems very little opportunity today to see any of

his work well reproduced. Which is a great shame; much of his work still looks

and feels modern, and makes a refreshing change from much of the conceptual and

experimental work that gets the attention of curators these days.